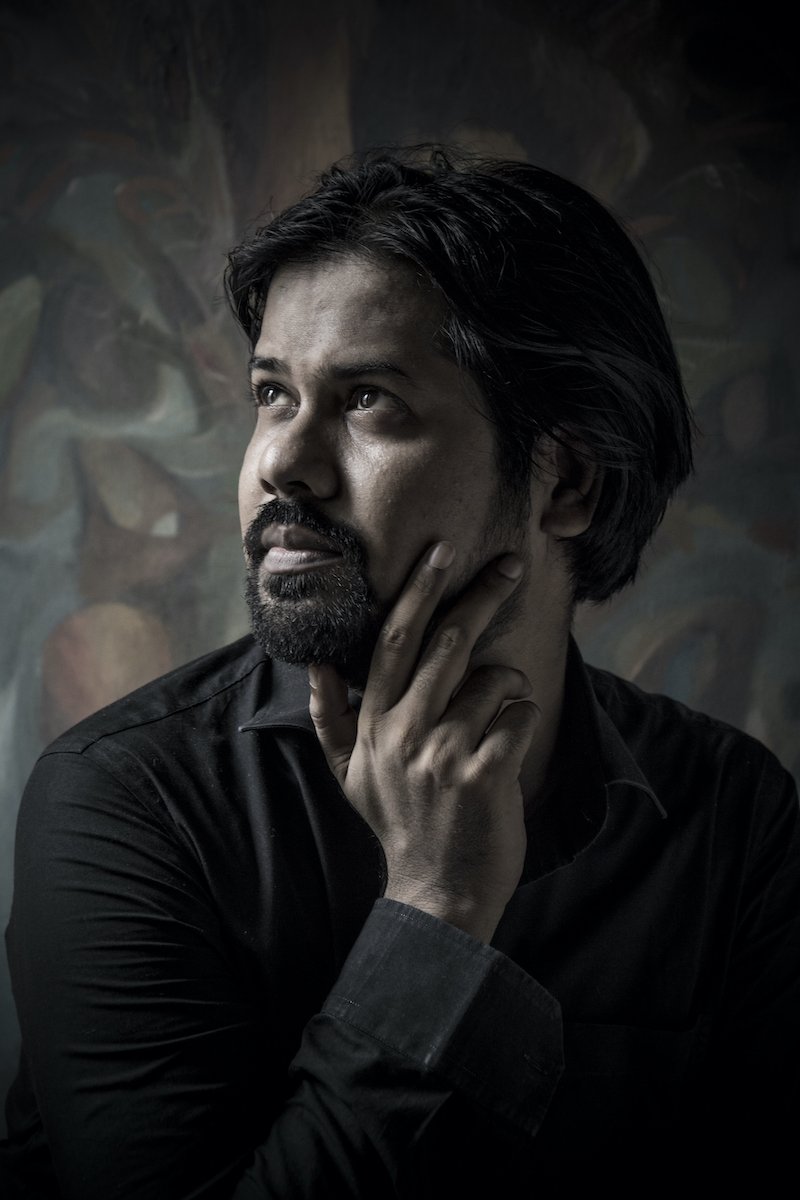

Interview - Shiraz Husain

Shiraz Husain is a visual artist and the founder of Khwaab Tanha Collective, which fuses literature and graphic design to make a statement. He has designed over one hundred book covers and has worked with Oxford University Press, Harper Collins, Hachette, Routledge Publishing, National Book Trust, Rajkamal Prakashan, National Council for Promotion of the Urdu Language, and Urdu Academy of New Delhi. He has exhibited his work in India, Turkey, the UK, and the UAE. Shiraz’s list of awards includes a children’s literature award from Room to Read for the book Lunar Soil and the Oxford Cover Prize for Brilliance in Book Design for Paaji Nazmein by Gulzar at the Jaipur Literature Festival.

His family originally comes from Naubat Khana and Mullano in Amroha and now resides in New Delhi.

1. Being a multidisciplinary artist, how do you approach different art forms?

During my school years, I began to learn about pop music and acoustic guitars in addition to writing stories and poems (doggerel of sorts) and creating pictures. My parents provided the space to experiment and experience without placing limits on what they felt I should and shouldn’t do. I continued trying and working with different art forms through to adulthood.

This has enriched my current way of working to this day. Now, when exercising my expertise as a graphic designer, I work with the courage of a painter. When I am in front of a canvas, the harmony of colours is not too dissimilar to my understanding of sounds, rhythm and music.

The design principles are not very different when applied across multiple disciplines. For example, if I am writing a story or composing music, then repetition, harmony, unity, gradation and contrast are important aspects which all come together and cannot be ignored.

2. Are there times when you create something from scratch using only software?

My college and university education were primarily grounded in manual and physical art. I recall using analogue cameras to capture images, developing them in a dark room and even completing social and product campaigns by hand.

We cannot ignore that it is 2024, and there is something to be said about the versatility and possibilities of using software to create digital art, which I have also used extensively.

Nevertheless, despite the demands and role of digital techniques, I very much like to work with my hands and re-model art during the post-production process.

3. What would be the percentage of commissioned works vis a vis vs own creative pursuit in your portfolio?

It isn’t easy to ascertain the boundary of both works in each percentage. Whether work is commissioned or uncommissioned, it remains part of your portfolio, practice and evolution as an artist.

Through commissioned works, I have come across wonderful clients, mainly from the publishing industries, where works include book covers and illustrations. I recall doing a cover for Gulzar’s Paaji Nazmein. The publisher provided a deadline of a single night, which I met. The following morning, the publisher informed me that Gulzar had approved and instructed me to proceed with the cover. The same cover later won the Best Book Cover award at the Jaipur Literature Festival. The point was that things worked out despite a tight deadline because I was familiar with his work and aesthetics. Understanding the subject, being familiar with the author’s style, and the frameworks under which the publishing house works are all part of developing not only the work but also creating that portfolio of the artist.

Research is, therefore, an important element of my work. Similarly, there is something to be said about the instructions and brief I am given, which ideally also has to hit a threshold with which I can work.

I have encountered various clients, authors, and editors who are either ambivalent or without any notions about their requirements. Sometimes, a conversation can flow as, “I want something different, something like this…do you know what I mean?” And my answer usually follows with, “No, I do not know, Sir/Ma’am. Would you please give some further details so we can work together to create something that speaks to you?”

We cannot take apart the dynamic of power and authority, which is always a subtext in any project. Unfortunately, when you are faced with the final decision-making authority, a project is likely to become dissatisfying at best or a failure at worst.

There have been times when excellent ideas have succumbed to death because of the combination of hierarchical behaviour at the intersections of limited understanding of the creative process and limited exposure.

My online commercial portfolio, therefore, has works that I like and have fondness for because I have spent the time forming a relationship with the project from its conception to execution. This comes only through the investment of time, background reading, and co-developing art.

4. You are also running an organisation. What has been your experience of working with other creative people?

Khwaab Tanha Collective has been the home for poster art, which I create solely and have creative control from conception to post-production. I have always, however, kept an open mind to suggestions from a close circle of people.

The Collective is widely known for poster art. However, the scope and depth of the work is much more profound. I collaborate regularly with people and organisations from various walks of life, including writers, artists, actors, musicians, and even individuals from public and philanthropic associations.

The internet is a weird and wonderful feat of society, where one can connect, produce work and grow in all dimensions. Examples of my work include the one-minute videos at Khwaab Tanha, such as an animation with Hollywood actor Riz Ahmed on his Toba Tek Singh song, Ali Fazal’s recitation of Bashir Badar’s ghazal over Baan G of Dastaan Live Band’s bases, Ghalib’s ghazal through Meyan Chang’s beautiful vocals and my visuals from Ghalib’s mazar in Nizamuddin.

Despite working in proximity with friends and artists from the creative community, there are often logistical challenges such as availability and synchronicity of time.

I am working on a nano series, Dono Dono (poetry in our daily life), with Ajeet Singh and Ipshita Palawat, both of whom are theatre practitioners and Bollywood actors. I particularly enjoy working with them, given their natural and quick reciprocation of the brief. There is something about flexibility, which is an additional dimension required to work effectively. It sometimes relies on experimenting or doing things we may not have done previously to make artistic co-creation possible. For example, Sameer Rahat, a young musician, kindly agreed to have his song shortened and adapted to fit the video for an episode of one of the Nano series. I am working on one of his Urdu Blues, Ghazal of Jaun Elia, and similarly, for the work to be co-created in a manner we both envision, my work will require the same adaptability and flexibility.

Returning to your question about experiences of working with other individuals, mine have generally been mutually satisfactory and enriching, which has been possible not only because of the underlying hard work we all put in but also the respect and admiration we have for each other’s work and craft.

5. AI has the potential to learn and emulate an artist, automating the creative process. Do you worry?

Yes. I sometimes worry; however, the worry is not about my work as a creative. The concern is about the concept of art, its execution and how it comes to be. I have seen in recent times that clients are not hesitant to make their book covers, logos and other miscellaneous works, which is positive regarding their engagement with their projects. However, of late, I have seen artificial intelligence depict works of a notorious painting of one painter in the style of another, for example, how the Mona Lisa would look if painted by Van Gogh, Modigliani, Picasso, et cetera. Such AI-created images are visually unappealing and disregard the nuance of a specific artist’s style and creation.

As far as painting is concerned, I remain optimistic. While one can copy the visual, there is also the element of physically engaging with the paint, brush, and canvas. It offers more, be it to the individual who is producing the imitation.

AI retains the potential to be important and, to some degree, revolutionary. However, there needs to be an ethical balance where the growth of our children’s intellect and imagination is not crippled by AI whilst we all remain aloof and constantly consumed by our phones.

6. What has been your most satisfying art project?

7. Do you have a dream project?

There are three: At least one poster in every Indian language, poetry posters in Braille, and a graphic novel on the adventures of literary Icons.

8. Does Amroha speak to you as Jaun Elia?

Shiraz Husain in conversation with Inam Abidi Amrohvi. (October 3rd, 2024)