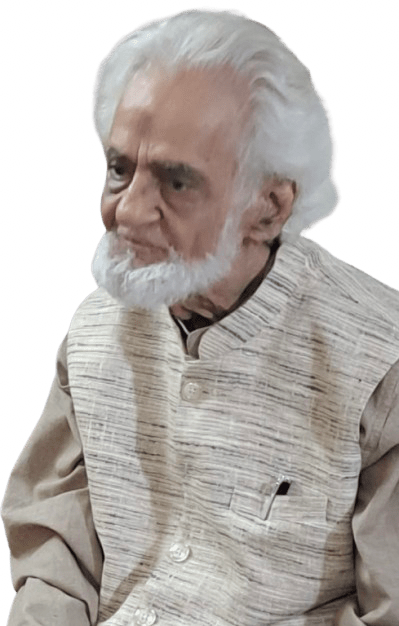

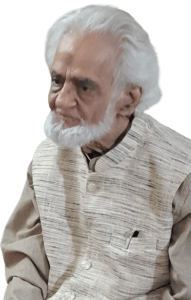

Interview - Ghulam Haider

Ghulam Haider has written over 32 books, which include 18 children’s storybooks. He received the first Sahitya Akademi’s Bal Sahitya Puraskar in 2010 for his short story collection Aakhri Chori aur Doosri Kahaniyan (the first Urdu writer to do so). In 1984, Haider established the ‘Bachchon Ka Adabi Trust’ (Children’s Literary Trust), which published 18 books and organised seminars and workshops to promote children’s literature.

Haider’s family comes originally from Mashratta, and later Pajdara. He now resides in Delhi.

1. You moved to Aligarh for higher education. There, you made history by being the first choir to sing the University tarana in 1954. What memories do you have of the day?

I studied for three years at Mansabia in Meerut before relocating to Delhi in 1944. From 1947 to 1951, I attended Jamia Millia Islamia, and from 1951 to 1957, I studied at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU).

Regarding your inquiry about the Aligarh Tarana, it is important to understand the political landscape of the city during that period. My friend Rahi Masoom Raza’s Aadha Gaon is the best representation of the atmosphere in Aligarh at that time.

Ahmad Saeed, my friend yet ideologically on the opposite side, was distraught that a nazm by Majaz, an ultra-progressive writer, was to be performed on a stage at AMU. A fellow student and leader of our musical group, Ishtiaque Ahmad Khan, had set Majaz’s Nazr-e-Aligarh to music. We were even threatened with physical violence if the nazm were recited in the union hall. Consequently, we gathered in secret at Safina Kothi, situated on the outskirts near a jungle on Medical Road, where Dr Maqbool resided. He also owned a harmonium. We practised there for a month in this quiet and secluded part of the city, completely unbeknownst to anyone. Three to four days before the actual date, news leaked that we would perform during the upcoming students’ union gathering on 17th October. We approached Dr Zakir Husain, Dr Noorul Hasan and Professor Moonis Raza, among others. On the 15th of October, we received an advisory that we should not do anything until dinner starts. We did exactly that!

The Stretchy Hall reverberated on 17th October, 1954, to the beautiful sound of “Ye mera chaman” for the first time in AMU. I was on the vocals with Ishtiaque Khan, Saleh Naiyyar, Ejaz, and Fasihuddin. Saeed approached us after five days and requested that we sing it again at the union hall.

AMU took part in the second youth festival at Shantiniketan in 1955. When we performed the tarana there, the audience was greatly impressed by the rendition and the fact that it was a university anthem.

2. Your first book ‘Paise ki kahani’ was published in 1973. How did the journey start?

Jamia Millia Islamia has done an outstanding job in children’s literature, to such an extent that it became a genre in its own right. Jamia was formed in 1920. By 1947, the university had printed over 300 books for children. A team of approximately 15 writers, which included Dr Zakir Husain, Ehsan, and Abdul Ghaffar Mudholi, were involved in this work. Children’s literature is in Jamia’s DNA. Mohammed Shafiuddin Nayyar, my teacher, was the most prominent name in children’s literature at the time. We were so energised by all this activity that I decided during my time at Jamia to write a book someday. My interest lay in prehistoric life with a focus on children.

I was mesmerised by Ashraf Saboohi’s ‘Banbasi Devi’. Two of my later books were influenced by it.

The book you mentioned was written between 1969 and 70, but due to some challenging circumstances, it was not published until 1973. It resulted from a few economics teachers’ profound impact on me at Jamia.

3. The translated collection of short stories, ‘Europe ki kuch nadir kahaniyaan’, is a selection of some great European works in your own words. But wasn’t it a translation itself?

Somewhere between 1960 and 1965, I came across “Great Stories of All Nations” by Maxim Lieber, a translation of selected Guy De Maupassant stories by Marjorie Laurie, a collection of German and Russian stories, the names of which I don’t remember. These are some fine, clean, and compelling stories from around the world. I have not found a better anthology of stories ever.

I decided to translate the entire collection, but I could only manage about 40, with only 24 making it into this book. Eleven of these stories are by Guy De Maupassant. The first story I read in that collection was “The Userer’s Will” from Italy, probably written in 1554, and later translated by me as “Soodkhwaar ka wasiyatnama.” There’s no parallel to Maupassant (French) and Manto (Urdu) in story writing.

You are right about it being a translation itself. But it was a beautiful translation and made my job easy. I was eager to bring it to an Urdu audience.

4. Sustainability is a buzzword today, but ‘Waqt ka Musafir’, which came out in 1992, addresses pollution in the year 2050. Your vision of 2050 appears to be already here. Do you agree?

I saw it already during the COVID-19 crisis. It was eerie to see some of the things I wrote in the book come to life right before my eyes. During a hospital visit, I could not make out the gender till the person spoke behind the PPE kit. One even had a tape on the forehead to hide it. In my book, I imagined that people were identified by a 10-digit code on their backs, which contained all the relevant information about them, such as their address, school and age. They are all covered under a special suit to save them from radiation.

The story revolves around two boys who engage in a debate on whether science has benefited humans over the last 200 years or has made things worse. One of the boys, Kamaal, favours science, while the other is against it. Kamaal loses the argument and comes back home dejected. He reads H.G. Wells’ Time Machine and is transported to another world in 2050, where he can do some amazing things.

5. You wrote on average one book every four years. But some writers come out with a book almost every other year. Do commercial obligations take preference over the creative process? What is your take?

When I began working in Delhi, my office was approximately 23 km from home. I commuted by bus for about 13 years and even wore a belt due to back pain. There were four school-going children at home. Finding time for writing was challenging, but I pursued it out of passion. That said, serious research requires a significant amount of effort, especially when you have to do it all alone. It’s difficult to source rare accounts and pictures when dealing with a 1500-year-old history (‘Daak ki kahani’) or 2000 a 2000-year-old history (‘Akhbar ki kahani’).

6. Tell us about the trust you formed for promoting children’s literature.

I left my job to focus on ‘Bachchon ka Adabi Trust’, an organisation to which I dedicated a substantial part of my professional life. The trust published 18 high-quality titles (of which 10 are on science), in which I take great pride. It received patronage from notable figures such as Hakim Abdul Hameed, Qamar Zaidi, Kartar Singh Duggal, and Malik Ram. The trust was also a culmination of my passion for promoting children’s literature and produced around eight writers. One of them, Shamsul Islam Farooqi, won the Bal Sahitya Puruskar (2010-2024) for his short story collection ‘Barf Ka Des Antarctica’. Although the trust is no longer operational, I did whatever I could.

7. You mentioned in an earlier interview that your father planted a tree in a property (land where the current Kotwali stands) that once belonged to your family. There would be other strong memories of the city. Yet, you spend less time in Amroha?

While researching my book ‘Rau Mein Rakhsh-e-Umar’, which is based on the letters of freedom fighter Syed Sher Ali, I extensively travelled in Amroha on a rickshaw with Gul Muhammad and Maulana Razan. Although I spent most of my life in Delhi, Amroha has always been in my mind, and my work is a testimony to this fact.

Regarding the Kotwali, a riot broke out in the city in 1902. My family lost several properties in the aftermath. The last time I visited Amroha, the tree was not there.

8. You wrote “raazi dile diwana na taqdeer na shad” in a book preface. Has anything changed now?

This line is from a rubai by Sarmad.

Raazi dil-e-divana ba-taqdeer na-shud

Faarigh za khayal-o-fikr-e-tadbir na-shud

Ayyam-e-shabab raft-o-baqiist havas

ma piir shudem-o-arzu piir na-shud

The mad heart did not submit to fate,

Nor was it freed from thoughts and planning.

The days of youth passed, but desire remained

I grew old, yet longing did not grow old.

This is also my philosophy in life. I’m currently researching another project on terrorism. The article will examine the various forms of terrorism and their impact on the global landscape. For example, how thousands of slaves carried stones on their shoulders during the construction of the pyramids. Holes were dug so that if they fall, they go into them. That was state terrorism.

I left my job to focus on ‘Bachchon ki Adabi Trust’, an organisation to which I dedicated a substantial part of my professional life. The trust published 18 high-quality titles (of which 10 are on science), in which I take great pride. It received patronage from notable figures such as Hakim Abdul Hameed, Qamar Zaidi, Kartar Singh Duggal, and Malik Ram. The trust was also a culmination of my passion for promoting children’s literature and produced around eight writers. One of them, Shamsul Islam Farooqi, won the Bal Sahitya Puruskar (2010-2024) for his short story collection ‘Barf Ka Des Antarctica’. Although the trust is no longer operational, I did whatever I could.

Ghulam Haider in conversation with Inam Abidi Amrohvi. (May 23rd, 2025)