Interview - Taqdis Naqvi

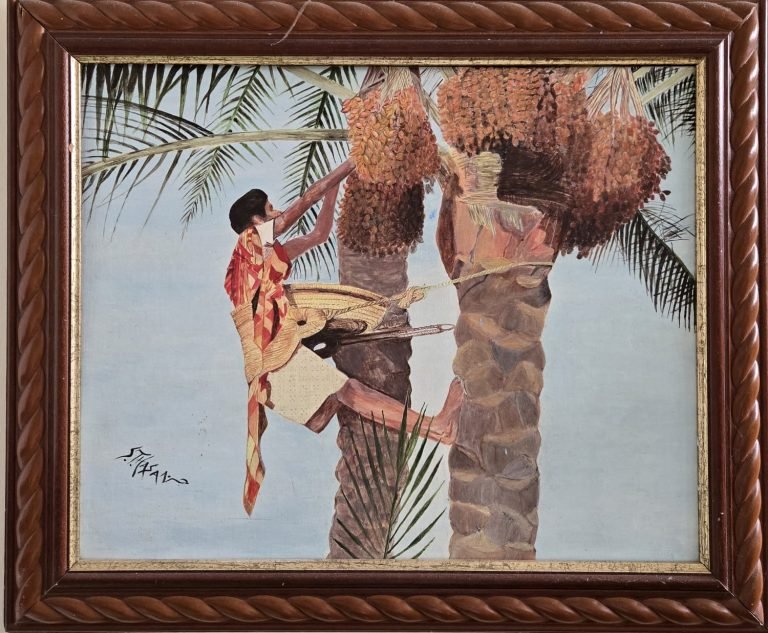

Taqdis Naqvi started writing in 1972, but professional engagements took over the passion. He resumed his craft post-retirement, focusing on religion, poetry and satire, and published several books in the process. A collection of his articles on wit and humour was published under the title Kharashein. His book on Amroha is scheduled for publication soon. He also paints as a hobby.

Taqdis Naqvi started writing in 1972, but professional engagements took over the passion. He resumed his craft post-retirement, focusing on religion, poetry and satire, and published several books in the process. A collection of his articles on wit and humour was published under the title Kharashein. His book on Amroha is scheduled for publication soon. He also paints as a hobby.

Originally from Haqqani, he now resides in Dubai, UAE.

1. You started writing as a hobby during your college days. How did the interest suddenly dry up before you took it up post–retirement?

I was born into a family known for both literary and religious traditions. My passion for teaching and learning later brought me to Aligarh, where—despite a strong literary inclination—I had to opt for the rather unliterary field of Commerce.

My interest in storytelling had already taken root during my school years. My first short story, “Andhere Chiragh” (Extinguished Lamps), was published in 1975 in the then well-known literary magazine Beeswin Sadi (The Twentieth Century). But the calculations of commerce soon outpaced the journey of literature. After completing my higher education, I joined the Faculty of Commerce at Aligarh Muslim University as a lecturer, which further slowed my literary pursuits.

A few years later, my career’s desert travels took me from Iraq to Dubai (UAE), where I eventually settled. After reaching the position of Vice President at a national bank and crossing the finish line of retirement, I embraced a peaceful seclusion — one that finally rekindled my passion for writing.

Although I continued writing short stories, with time I also began exploring humour and satire, finding in them a fresher, more expressive path. My essays on political, social, and moral issues have appeared in many prominent Indian literary journals.

2. What drives you to pick up a subject for prose and poetry?

By choice or by fate, I never aligned myself with any literary movement. In my brief literary life, I have always believed in “literature for life” rather than “literature for literature’s sake.” I never wrote simply for the sake of writing — only when a subject itself stood before me demanding to be written.

Maintaining a clear line between my professional and literary lives spared my pen from any pressure. I may not have written much, but I am content with what I have written.

Through my writings, I have tried to address social, moral, and political issues under unconventional titles — ones that instantly attract the reader’s eye. Titles such as “Qabr ka Intekhab” (The Choice of a Grave), “Marsiya-e-Qalam” (The Elegy of the Pen), “Imtihaan ke Jootey” (The Shoes of Examination), “Online Kahili Service” (Online Laziness Service), and “Naam ka Bukhaar” (The Fever of Names).

Perhaps that is why my writing often leans toward social reform, blending satire with a sense of seriousness, ensuring that humour’s bright colours never overshadow its deeper purpose.

I write mostly ghazals. I reintroduce words in my poetry that either represent Amroha culture or are no longer in use. For example:

Diyot (lamp with a wooden stone)

Umeed-e-sehra mein diyot bacha raha tha charaagh

Hawaye-tund ka dam ghut gaya bujhaane mein

Jajam (linen spread)

Le ja uthake chaand tu yeh apni chaandni

Noor-e-khayaal-e-yaar ki jajam bichhai hai

Palla (lower end of robe)

Apne palle na padi baat kabhi nasih ki

Kab se peeche hai pada jhaad ke palla mere

Ghadonchi (wooden stand for pitchers)

Ghadonchi zabt ki ab tooti hai

Gharaa dil ka hua labraiz gham se

Turpun (stithes)

Kis mahaarat se mere hont hain silwaye gaye

Nazar aate nahin bakhie talak is turpun mein

Khotey (slit in dress)

Daman-e-dil sambhaal kar rakha

Phir bhi do chaar khote aa hi gaye

Pat (door plank)

Kewaad khol ke baithe the hum zamane se

Hawaye waqt ne pat khol kar kiya pat hai

Cheena (torned dress)

Us ne cheena hai mera sabr-o-qarar

Chaak-e-dil aur chhe na jaaye kahin

3. How difficult is it to write satire in current times when dissent is frowned upon?

I chose satire and humour over fiction because today’s fast-changing social and political landscape has chained the writer’s pen in unseen shackles. Only satire and humour possess that subtle power through which one can draw attention to the thorns of society while hiding them among flowers. Satire performs the surgery, while humour serves as the balm to heal the wounds.

A collection of my satirical essays titled “Kharashein” (Scratches) has already been published, while two more books — a short story collection “Sookhe Peer Ki Chhaon” (The Shade of a Withered Tree) and another volume of humorous essays titled “Chutkiyaan” (Pinches) — are currently in press.

4. As a long–term Indian expatriate, does writing about your homeland offer a sense of fulfilment?

Yes, it is indeed a source of deep satisfaction for me that despite spending most of my life in Dubai, I have never, even for a single moment, severed my emotional connection with my beloved homeland. In one of my writings, I have also acknowledged that even after living away from my homeland for more than five decades, Amroha still resides within me. The themes of my writings and stories often reflect glimpses of Amroha. The subjects of my stories and the characters in my essays are inspired by the environment of Amroha and Aligarh, which brings me a sense of fulfilment.

A person’s identity is shaped by their homeland and family. Recognising this truth, I have written a book in two volumes titled ‘Amroha Meri Pehchan’ (Amroha my Identity) and ‘Taqdees-e-Ansab’ (Sanctity of Lineage), which is currently under publication and, God willing, will soon be presented to my fellow countrymen.

5. Was your book Akhirat Ka Safar (The Journey of the Hereafter) inspired by Hayat Ba’ad Al Maut (Life After Death), written by your family elder, Maulana Syed Zafar Hasan?

Immediately after concluding my professional career and resuming writing after almost 35 years, I first felt the responsibility of being the sole literary heir of my grandfather, Maulana Syed Zafar Hasan. Hence, I initially focused on religious writings, leading to the publication of books such as Anwar al-Masumeen and Anwar al-Qur’an.

All the essays in these books were written with the religious challenges our youth face today in mind. Among various topics, one that has always intrigued young people is the concept of the Hereafter, or Life After Death. Having experienced similar curiosity myself during my youth, I had resolved that, if Allah granted me the ability, I would write a comprehensive book on this vital subject in a simple, accessible manner.

My interest in this subject also stemmed from the fact that no contemporary book on this topic had come to my attention in modern Urdu literature. However, while preparing material for the book, I faced two challenges.

First, although there are countless narrations related to the Hereafter, presenting only authentic and credible ones to the younger generation—especially when today’s youth seeks validation of every belief in the Qur’an—was not easy.

Second, most earlier works on the subject were in Arabic or Persian, and the limited Urdu material available was not easily comprehensible. Therefore, I decided to present all the stages of the Hereafter based on Qur’anic verses, so that young readers could understand and accept them without hesitation.

By the grace of Allah, this endeavour was completed, and the book reached readers. The distinctive feature of this book is that it discusses every stage of the afterlife, step by step, in the light of the Qur’an.

6. As a scholar of Islam, what role do you see for ever–evolving cultural practices? For example, public display of charity, when the Quran, in verse 29 of Surah Al-Isra, clearly says otherwise.

For any society, change or continuous transformation is considered a sign of life. Our cultural and moral values are no exception to this process. What is required, however, is that every individual in society takes responsibility for embracing the positive aspects of such change, promoting them, and taking timely and effective measures to counter the adverse effects—so that reform does not become difficult.

Naturally, in this process, the responsibility of religious and literary scholars and educators increases. It is their duty not only to identify harmful cultural shifts through their speeches, writings, and actions but also to propose measures for reform.

As a responsible writer, I have tried—through my writings—to address the doubts and misconceptions about religious beliefs that have emerged among the youth due to the modern education system and social media. At the same time, I have sought to highlight social and moral issues through the effective medium of satire and humour. Most of my stories also revolve around social concerns.

Regarding charity, the Qur’an commands both open and secret giving. Public charity encourages others to give, while secret charity prevents arrogance and protects the dignity and honour of those in need. In the Qur’an, Allah declares in Surah Al-Baqarah (Verse 271):

“If you give charity openly, it is well; but if you give it in secret to the poor, it is better for you.”

7. Is there a future for printed books, considering how AI is generating creative content? Do you see a way out?

Artificial intelligence, while making human progress easier, has also created many challenges. AI can indeed generate content on any subject and present it in any format; however, literature and art are exceptions, for both embody the artist’s and creator’s spirit, which AI cannot replicate.

That said, AI can still be a helpful tool for providing material and references for writing. In any case, AI itself is still evolving, and much work remains to be done in this field—its actual impact will only become clear in the future.

8. What’s your lasting memory of Amroha?

Although it has been almost 55 years since I formally left my homeland, my bond with Amroha has never been completely severed, as I have continued to visit regularly. During my stay in Aligarh, I used to visit Amroha almost every month, and after moving to Dubai, I made it a point to visit nearly every year. Each visit would fill my being with the fragrance of its soil.

Since my parents resided in Amroha—and are no longer in this world—every moment I spent there with them remains illuminated by their memories. Those memories are my most lasting and precious treasure.

Taqdis Naqvi in conversation with Inam Abidi Amrohvi. (November 6th, 2025)