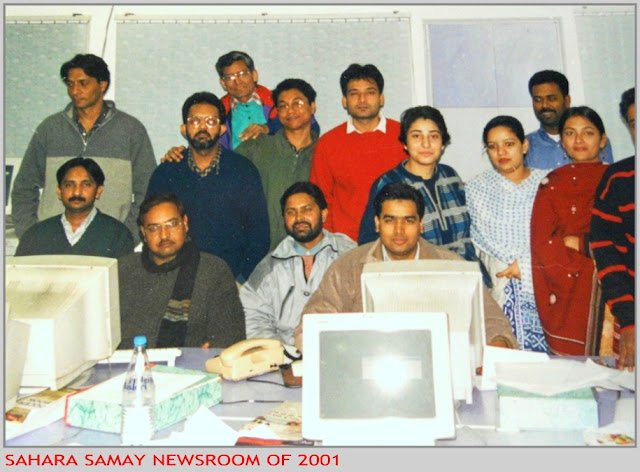

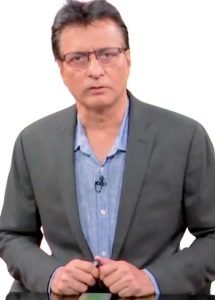

Interview - Mansooruddin Faridi

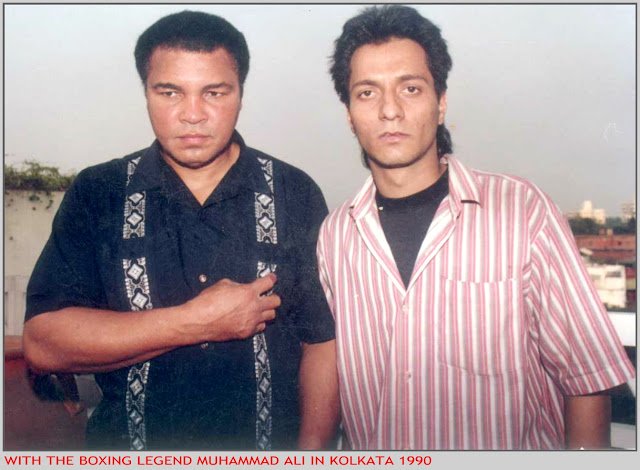

Mansooruddin Faridi is a journalist whose career spans nearly four decades across print, electronic, and digital journalism. His association with media outlets such as Nai Duniya, All India Radio, and Sahara Samay led to interviews with Muhammad Ali, Salim Durani, Farooq Abdullah, Inder Kumar Gujral, Mamata Banerjee, and many others, as well as coverage of important events. He is currently serving as the Editor of Awaz The Voice Urdu.

Mansooruddin Faridi is a journalist whose career spans nearly four decades across print, electronic, and digital journalism. His association with media outlets such as Nai Duniya, All India Radio, and Sahara Samay led to interviews with Muhammad Ali, Salim Durani, Farooq Abdullah, Inder Kumar Gujral, Mamata Banerjee, and many others, as well as coverage of important events. He is currently serving as the Editor of Awaz The Voice Urdu.

Originally from Saddo, he now lives in Delhi.

1 You worked in print, electronic and digital media, which one did you find the most challenging?

Look, I have witnessed that era of journalism when being associated with a news agency was considered a matter of prestige for any newspaper. That was also the time of hand-delivered service. There was a period when a delivery man from PTI (Press Trust of India) would arrive on a bicycle, drop a bundle of PTI news at the newspaper office, and leave. This process used to happen every two hours, so by the time news reached the newsroom, several hours had already passed.

In those days, litho printing was used, which involved stone plates. This system continued until around 1979 or 1980. Gradually, improvements came—first sheet offset printing, and then web offset, which brought about a revolution. Along with this, news agency teleprinters reached newspaper offices, greatly accelerating the flow of news.

Let me tell you, this was also the era when people listened to the BBC and then wrote news stories for newspapers, because there was no other source of detailed information. There would hardly be any Urdu or Hindi newspaper in India that did not rely on the radio for news gathering. However, the arrival of the teleprinter changed this entire situation.

I mention this journalistic format because, until then, journalists faced only one kind of pressure. The front page of a newspaper was a matter of honour. The later a newspaper’s final edition went to press at night, the more successful it was considered, because it carried the most up-to-date news. After sending the last copy to the press late at night, journalists could go home, sleep, wake up in the morning, have breakfast, and eat their meals in peace.

But when electronic media emerged, people began folding up their four-page newspapers and sitting in front of their television sets. This marked a major shift—the era of “breaking news.” In electronic media, whoever broke a story first became number one. This race turned journalists, in one way or another, into racehorses.

With the advent of television channels came the culture of prime time. After eight o’clock at night, watching news channels became a routine for people. But behind this were the relentless efforts of hundreds of people working in electronic media. On one side, reporters would rush back to the office, while on the other, cameramen would send their footage to the newsroom through couriers. Eventually, with the speed of the internet, these difficulties were overcome, and major transformations occurred in electronic media.

Interestingly, we, too, believed that electronic media represented the peak—the fastest form of journalism. But the emergence of digital media reduced both print and electronic journalism to relics of a bygone era.

Digital journalism has given wings to the world of news. News is no longer anyone’s private property. No one waits for a newspaper or a news agency for information now. Because of social media, news reaches your mobile phone even before newspapers or news channels can. This situation has made digital journalism the fastest—and also the most stressful—form of journalism for journalists.

The time has passed when news would arrive and then be reported. Now the mobile phone is in your hands; wherever you are, you can upload news from there. Digital journalism has become a moment-to-moment existence, unmatched in speed. I can truly say—we have travelled an astonishing distance from where we once were.

2. How different was it working in Calcutta compared to Delhi?

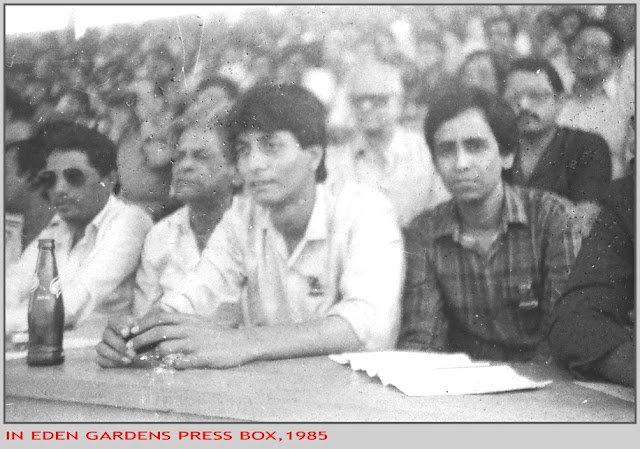

The difference was as profound as the difference in temperament between the two cities. In Kolkata, newspapers had a life of their own—there was a sense of calm and continuity; speed did not carry the importance it does today. It was there that I began my journalistic career in sports reporting. When Mohammad Azharuddin scored his first Test century at Eden Gardens, Kolkata, I was a witness to it as well—my very first Test match as a reporter.

Later, crime reporting was added to my responsibilities. After some time, I began covering sessions of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly. Soon after, I was swept up by the fever of film festivals. Following the demolition of the Babri Masjid, when riots broke out, I considered it my fundamental duty to patrol curfew-bound, riot-affected areas.

In fact, in Hindi and Urdu newspapers, no single beat was reserved for any one reporter. That is why those covering sports could be seen reporting on films; those covering films could be found on the crime beat; and crime reporters were also found in the Assembly.

As for journalism in Delhi—the centre of the country’s political life—when I moved from Kolkata to Delhi, the first publication I worked with was Akhbar Naujawan, edited by Syed Abid Anis. He is credited with publishing India’s first quality magazine on youth affairs and sports. Its office was located at ITO, and it was with this magazine that I began a new innings in Delhi.

However, in 1995, I stepped into Nai Duniya as a weekly publication. After working in daily journalism in Kolkata, the experience of a weekly was entirely new. The focus shifted from straight news to articles, interviews, and special reports—an altogether different and enriching experience.

Nai Duniya has its own history. Shahid Siddiqui was its editor, carrying forward the legacy of his father, Maulana Wahiduddin Siddiqui. There is no doubt that I had learned the basic alphabet of journalism at home, but the finer nuances—the dots and vowels, so to speak—I learned at Nai Duniya.

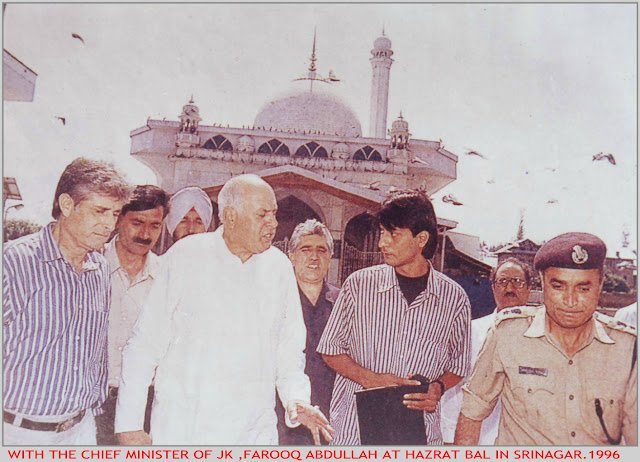

During my time there, I conducted countless interviews, including those with former Prime Minister I. K. Gujral; former Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah; his son Omar Abdullah; Saifuddin Soz; senior leaders of the Hurriyat movement, such as Syed Ali Shah Geelani and Mirwaiz Umar Farooq; Syed Shahabuddin; and Maulana Saad, the head of the Tablighi Jamaat.

Beyond this, whenever any turmoil erupted at Aligarh Muslim University, it seemed my number would come up. As a result, I had several meetings and interviews with the then Vice-Chancellor, Professor Mahmood Rahman.

3. As somebody who has covered minority affairs extensively, what is your take on the issues that make the most noise? Do you feel unnecessary coverage hampers progress?

Whenever the issue of minorities comes up, an uproar automatically begins. The time has passed when one could speak about minorities and be actually listened to. There was an era when education and other issues were discussed seriously; governments used to set up commissions, their reports would be published, and some decisions would follow. But whatever was done produced very little real impact—mostly symbolic results.

Today, whether the issue concerns reservations or employment, it is no longer treated as a genuine problem but has become a dispute. That is why, even after the judicial verdict on what became the country’s biggest dispute—the Babri Masjid case—Muslims still face no shortage of problems. The prevailing conditions and existing policies indicate not improvement, but further deterioration.

Another important point is that even governments that once spoke in favour of minorities or Muslims are now stepping back due to political calculations of profit and loss. This is a dangerous sign.

4 Of all the interviews conducted by you, which one was the most memorable? Is there any personality whom you wanted to interview but couldn’t?

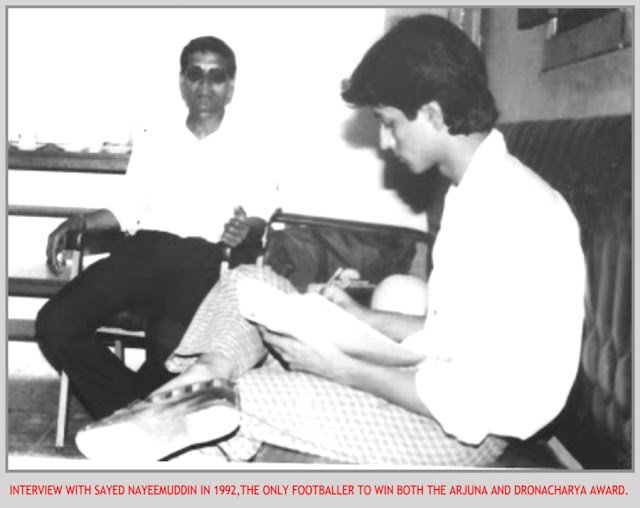

Regarding interviews, I believe that at different stages of life, they carry different levels of interest and importance. There was a time when I covered sports; during that period, I interviewed well-known figures such as former Pakistan captain Asif Iqbal, India’s wicketkeeper Syed Mujtaba Karimi, former all-rounder Salim Durani, and Mohammad Azharuddin.

After moving to Delhi and working with Nai Duniya, I spent a period covering Kashmir extensively. This was during the 1996 Assembly elections, when elections were resumed in Kashmir after a long gap. At that time, I conducted interviews with Farooq Abdullah, Saifuddin Soz, Umar Farooq, Syed Ali Shah Geelani, and several other Kashmiri leaders. I also did a long interview with former Prime Minister I. K. Gujral.

You may be surprised to learn that, while I conducted many interviews, there was one that, in my view, no one else in the world has done to this day. That was the interview of Maulana Saad Sahib, the head of the Tablighi Jamaat—an organisation whose leader traditionally stays away from the media. Following the internal rift and crisis within the Tablighi Jamaat, Maulana Saad gave an interview that was published in Nai Duniya. In my opinion, that was probably the first and the last time Maulana Saad ever spoke to a journalist.

5. There’s a lot of activism in the work that you do. Do you feel the role of a journalist goes beyond reporting facts?

Look, the role of a journalist is not limited merely to reporting facts. Journalism, in reality, serves as a strong bridge between society and power. A journalist becomes the voice of the people, highlighting issues that are often ignored. By bringing the truth to light, the journalist holds powerful circles accountable.

A responsible journalist awakens public consciousness against social injustice and gives voice to the pain and suffering of the oppressed and marginalised. Journalism plays a vital role in shaping public opinion. A journalist teaches society to distinguish between right and wrong.

By standing against rumours and falsehoods, the journalist strengthens the truth. The journalist’s pen is essential to democracy’s survival. Journalism not only delivers news; it also explains the background and the consequences of events.

A conscientious journalist places national interest above personal gain and considers it a duty to speak the truth even in difficult circumstances. Journalism is an effective instrument of social reform. A journalist also provides intellectual guidance to the younger generation and preserves historical facts.

The role of a journalist builds public trust and keeps alive the tradition of questioning within society. Journalism is not merely a profession but a responsibility. That is why a journalist’s role cannot be confined to reporting alone.

6. Your father was a prominent Urdu journalist and a Gandhian. Are you trying to carry forward his legacy?

I learned the principles of journalism from my late father, and how to live a simple life as well. However, I cannot claim to have truly proved myself a worthy guardian of that legacy. My father spent his life wearing a simple khadi kurta and pyjama.

There is an incident from my wedding. When I became the groom, I asked my father whether he looked better as a groom or I did. He replied that he did not know whether he looked good or bad, but that he had looked like a Muslim.

In truth, that was a different era, and this is a different one. Still, the moral values I learned—and the instinct never to sell my pen—have remained intact. Ultimately, it is up to one’s conscience whether one turns this profession into a service or a business.

7. People complain about news propaganda these days, but this is not something new. State broadcasters have always aligned with the government in power. What has changed then?

There is no doubt that in every era, there has been pro-government media. However, it is also a fact that, in the past, some newspapers at various times could seriously embarrass the government, put it under immense pressure, or even force it to back down. That was the kind of journalism that flourished in those times.

But times have changed. In the present climate, speaking against the government is cast as speaking against the nation itself. In mainstream media, the forces that once held the government accountable—by drawing attention to its weak policies and flawed decisions—have all but disappeared. The situation has become entirely one-sided. Now there is only praise-singing to the extent of servility.

This is why a clear difference can be seen between journalism of the past and journalism today. Today, there is not a single newspaper or television channel that can be called a challenge to the government, or whose independent journalism we can openly salute. That is why it feels that propaganda journalism has crossed the danger line.

8. Change is permanent! Do you want something to never change in Amroha?

Amroha’s name, my late mother used to say, should be uttered only after performing ablution. It is difficult to put into words the love we have seen for Amroha. Although we spent our childhood in Kolkata, we visited Amroha every year, and those memories remain vivid to this day.

As for change, certainly not everything; however, a great deal has changed in Amroha. Houses from earlier times have now been transformed into new buildings. At the same time, some old ruins can still be seen just as they were—most notably the Saddo Mosque.

Regarding your question, what truly worries me is the changing of names. A new wave is sweeping the country, a new culture is taking shape—one that involves renaming cities and roads. My only prayer is that the city remain called Amroha, because everything lies in its name.

Mansooruddin Faridi in conversation with Inam Abidi Amrohvi. (January 10th, 2026)